The advent of Generative AI (GenAI) is triggering a paradigm shift in software engineering. We are moving from a world dominated by deterministic logic, where every line of code executes a precise instruction, to an ecosystem where we integrate components based on probabilistic models.

This transition forces us to radically rethink architectures, patterns, and best practices, especially as we put AI agents into production without a solid understanding of how they work and how to control them. The risk of exposing critical decision points to a non-deterministic system without adequate control mechanisms is one of the greatest challenges we face.

Probability

Probability quantifies uncertainty: it assigns a number between 0 and 1 to how likely an event is.

- 0 = impossible

- 1 = certain

- Values in between compare relative likelihoods

Example with a dice

Roll a fair six-sided dice. The possible results are {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}, this is called the sample space.

The probability of each outcome is 1/6, since the dice is fair and all outcomes are equally likely.

We can indicate the probability as a function with the letter P, as follows:

Roll a fair six-sided dice. The possible results are {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}, this is called the sample space.

The probability of each outcome is 1/6, since the dice is fair and all outcomes are equally likely.

We can indicate the probability as a function with the letter P, as follows:

- P(roll = 3) = 1/6

- P(roll is even) = P(roll = {2, 4, 6}) = 3/6 = 1/2

From this example, we can define the probability as the number of favorable outcomes over the number of total possible outcomes.

The probability can be also expressed using percentage, for example P(roll is even) = 50% that means we expect half of the rolls to be even (in a long running).

Probability can change if we know extra information. This is called conditional probability. For example, what is the probability of an even result given the roll is > 3?

- Outcomes > 3: {4, 5, 6}

- Even among these: {4, 6}

- P(even | roll > 3) = 2/3

We use the symbol pipe | to indicate conditional probability. It reads as "the probability of even given roll > 3".

For a great introduction about probability, I suggest this free course from Coursera, An Intuitive Introduction to Probability by Prof. Karl Schmedders.

Probabilistic models

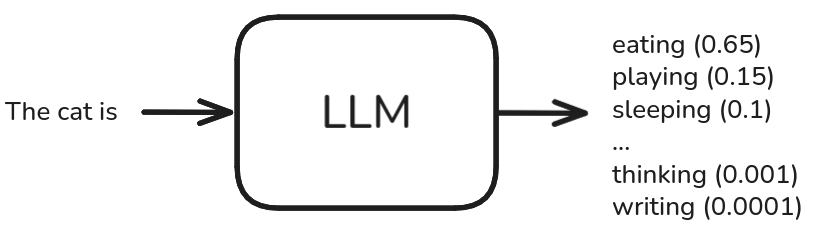

Unlike traditional software, Generative AI models like Large Language Models (LLMs) are inherently probabilistic. Instead of producing a single, certain result, they assign probabilities to all possible outcomes. In the case of LLMs, these probabilities determine how "tokens" (words or parts of words) are generated in sequence, based on the preceding context.

LLMs generate sentences by completing a given text, known as a prompt. For example, with the prompt "The cat is", an LLM might predict the token "eating", resulting in the sentence "The cat is eating".

The choice of the next token depends on the probabilities assigned to each candidate token, given both the prompt and the tokens generated so far. This is often represented as a probability distribution over the model’s vocabulary, where each token has a specific likelihood of being selected as the next word in the sequence.

In the figure above, the LLM generates a distribution of probabilities for each token. Applying different strategies for choosing the next token, we can generate different sentences. For instance:

- The cat is eating

- The cat is playing

- The cat is sleeping

- ...

The most probable token is “eating”, but the model can also generate “playing” or “sleeping” with lower probabilities. Typically, LLMs use the top-p sampling algorithm, which selects tokens from the smallest set whose cumulative probability is at least p. In our example, if p = 0.9, the smallest set of tokens is { “eating”: 0.65, “playing”: 0.15, “sleeping”: 0.1 }, since their combined probability reaches 0.9. This means the model may choose any of these three tokens.

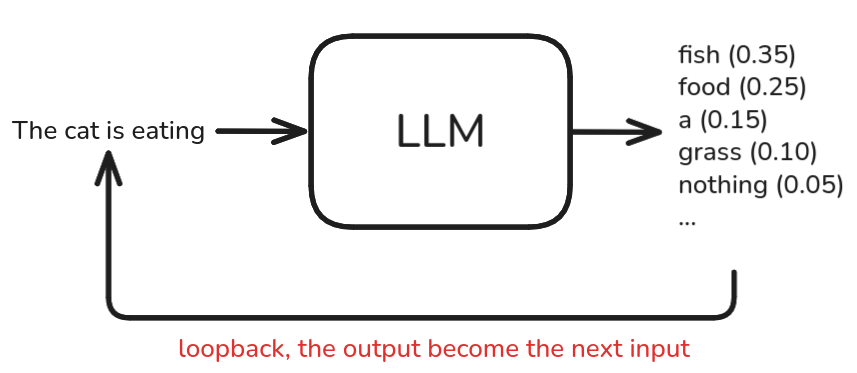

To generate a complete output, the algorithm repeatedly takes the generated text as input and continues producing tokens until it reaches a predefined length or meets a stopping criterion.

Managing uncertainty

The accuracy of modern LLMs has improved in recent years, but sometimes the answers they generate can still be incorrect. But what exactly do we mean by an “incorrect” answer? After all, the output is just a sentence—so how do we decide whether it’s correct or not? The answer depends on context. An LLM might produce a response that sounds plausible but is factually wrong, or it may even hallucinate information.

The model itself has no awareness of whether its answer is correct. It simply follows probabilistic patterns that guide how a sentence is completed.

For example, the best LLMs achieve about 87% accuracy on the GPQA benchmark, which means they fail in around 13% of cases. And that is only for one specific benchmark. LLMs will never achieve 100% accuracy across all possible use cases.

This means that error is an intrinsic feature of these models. The challenge for developers is no longer just preventing logical bugs, but estimating and managing this probability of error. Some approaches to estimation include:

Benchmarks: standardized question-and-answer sets, like the GPQA (Graduate-Level Google-Proof Q&A Benchmark), can be used to measure a model's accuracy on complex tasks.

LLM as a judge: a second LLM can be used to evaluate the quality and correctness of the answer generated by the first, often against a pre-made set of questions and answers.

Verifying the output: if the output is a code, it can be executed to check its correctness. For instance, if we generated a SQL statement from a natural language query, we can run the query and in case of errors, we can apply a retry mechanism, asking the LLM to rewrite the original question to get another chance.

The New Architecture: Pillars of AI Agents

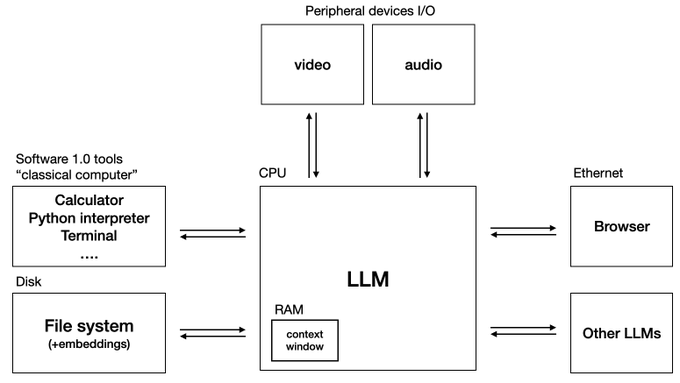

Modern software architectures are evolving to leverage LLMs not just as text generators, but as reasoning engines for autonomous agents.

Andrej Karpathy recently highlighted the importance the importance of these advancements in the presentation Software in the era of AI. He introduced the concept of LLM OS, a new architecture in which the LLM functions as the CPU, the central component responsible for managing both data and computation.

This idea forms the foundation of Agentic AI systems, which can orchestrate complex, multi-step tasks and interact with the outside world. In an Agentic AI application, we delegate the decision-making around task execution to an LLM. A key challenge is determining how and to what degree of autonomy we want to delegate control to the LLM.

In other words, we are trying to answer the question: How can we build autonomous software systems?

What capabilities of LLMs can we leverage to build Agentic AI applications? Some of the key properties include:

-

Task Decomposition: The most advanced models, often called Large Reasoning Models (LRMs), are trained to break down a complex problem into simpler, more manageable sub-problems. A common architectural pattern that implements this concept is ReAct (Reason + Action), a loop where the agent first "reasons" about the next step (Reason) and then executes an action to achieve the goal (Act).

A common architectural pattern that implements this concept is ReAct (Reason + Action), a loop where the agent first "reasons" about the next step (Reason) and then executes an action to achieve the goal (Act).

More details in Shunyu Yao et al., ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models, 2022.

Tool Invocation: One of the most revolutionary capabilities of LLMs is their emergent ability to "call tools"—generating structured function calls when they realize they need external data or actions to complete a task.

The process works in a 3-steps dance:

- The LLM recognizes the need to use a tool based on the function's description and parameters. It suggests the function call with the correct arguments, extracted from the user's request.

- An external, deterministic, and controlled system executes the function (e.g. a Python function). This is a crucial architectural control point where validation logic, human feedback, or security checks can be inserted.

- The result of the execution is fed back into the LLM's context, allowing it to formulate an informed and accurate final response.

More details in Enrico Zimuel, Tools calling in Agentic AI, 2025.

-

Self-Correction based on Feedback: This concept is tightly linked to the ReAct cycle. After executing an action (Act), the agent "observes" the result. This output serves as feedback, which is integrated into the agent's context and informs the next reasoning step (Reason). This allows the agent to dynamically correct its action plan, learning from the outcomes of its operations to achieve the final goal more effectively.

More details in Renat Aksitov et al. ReST meets ReAct: self-improvement for multi-step reasoning LLM agents, 2023.

Redefining best practices

Putting such complex and non-deterministic systems into production requires a shift in mindset, moving beyond intuitive "vibe-testing" to embrace a rigorous engineering approach.

This has given rise to a new operational methodology: Agent Operations (AgentOps), which adapts the principles of DevOps and MLOPs to the unique challenges of AI agents.

A robust evaluation framework, as proposed by AgentOps, must operate on multiple layers:

Component-level evaluation: Deterministic unit tests for tools and API integrations to ensure they are not the source of errors.

Trajectory evaluation: Analysis of the agent's reasoning process correctness. Did the agent choose the right tool? Did it extract the correct parameters? Was its "chain of thought" logical?

Outcome evaluation: Verification of the semantic and factual correctness of the final response. Is it helpful, accurate, and based on verifiable data (grounded)? Here, techniques like Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) are fundamental to connect the model to reliable data sources and reduce hallucinations.

System-level monitoring: Once in production, it is essential to continuously monitor performance, tool failure rates, latency, and user feedback to detect behavioral drift.

Conclusion

Software development in the GenAI era requires us to become architects of systems that orchestrate probabilistic reasoning engines. Success no longer depends solely on writing flawless code, but on our ability to govern uncertainty. This demands a mastery of agentic architectures built on task decomposition, tool invocation, and self-correction.

Above all, it requires adopting disciplined engineering practices like AgentOps to ensure reliability, security, and control.

We need more developers in the age of AI, not fewer.

Shalini Kurapati PhD, CEO of Clearbox AI

I agree with Shalini Kurapati: we'll need more developers in the future but their skill sets will evolve to include new professional roles, such as the Context Engineer, someone who specializes in providing the right context for models to operate effectively.